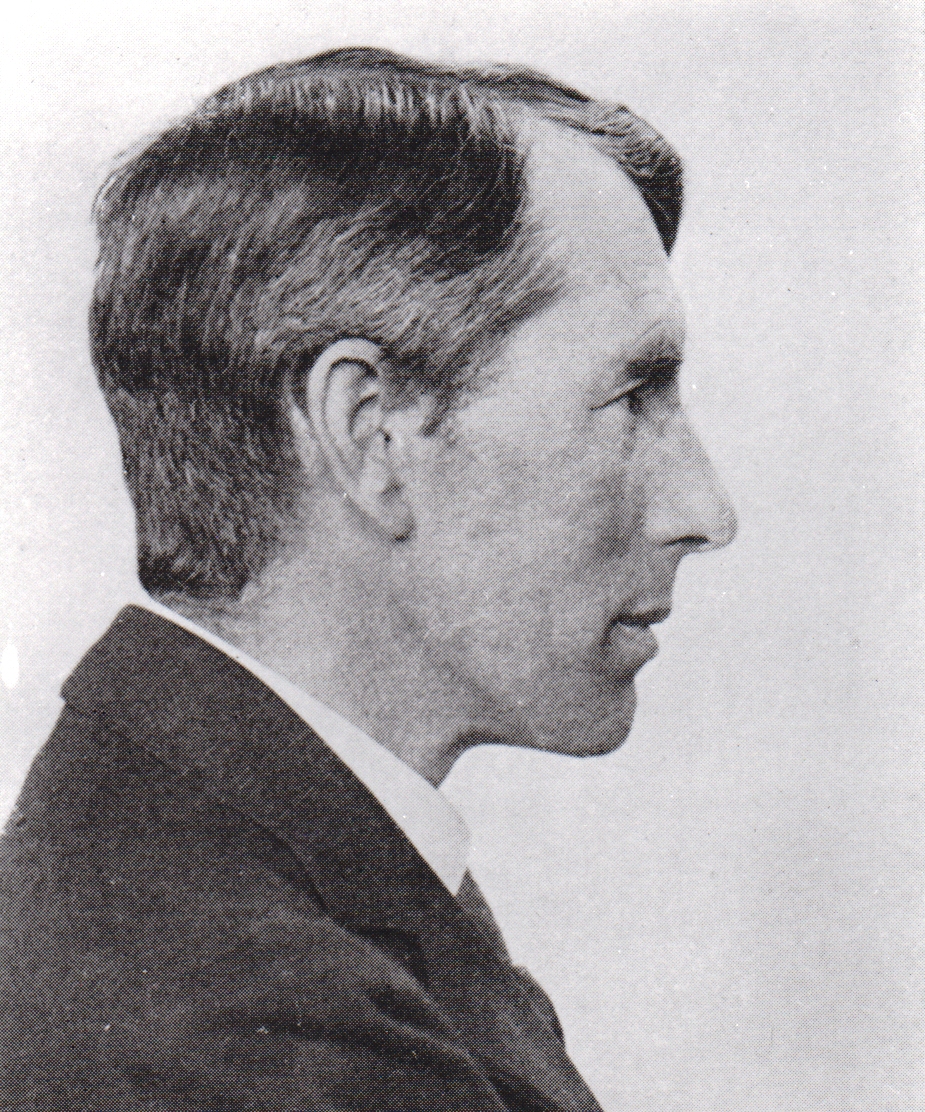

Walter Godfrey – The Society’s Chairman & Honorary Editor 1928-1960

Volume XXII of the Society’s currently five-yearly ‘London Topographical Record’, published in 1965, carries an obituary by Sir John Summerson on Walter Hindes Godfrey CBE who had died in 1961. Architect and antiquarian, between 1941 and 1960 he was the first Director and the inspiration behind the foundation of the National Buildings Record, the basis of today’s English Heritage Archive. Walter Godfrey’s leadership, as Chairman and Honorary Editor of the London Topographical Society from 1928 until 1960, almost single-handedly kept the Society afloat during the supremely difficult period of the Second World War when he managed to produce a publication for every year except 1943.

The amazing list of his published works, compiled in the same volume of the Society’s Record by Majorie B. Honeybourne, who succeeded him as editor, comprises 12 books, 13 pamphlets, 21 Sussex church guides, editorial control of 37 publications including six editions of the ‘London Topographical Record’, 146 general articles, 57 London articles, 234 Sussex articles, 50 reviews and 17 illustrations and plans.

Walter Hindes Godfrey was born in London on 2 August 1881 the eldest child of Walter Scott Godfrey, who at the time was conducting a small wine business. His mother was Gertrude Annie Rendall of Bristol. The elder Godfrey gave up his private business in 1882, joined another firm and then, in 1884, became manager to W.H. Chaplin and Co. of Mark Lane. He was a man of uncommon forcefulness and energy and, as his son described him, ‘self-centred and self-conscious to a degree almost unbelievable’. The first twenty-one years of Walter Godfrey’s life, as he has recorded them in the memoir written for his family, present the picture of a household dominated by the father’s ruthless idealism, first of a religious kind and later agnostic and socialist. In 1888, when Walter was seven, his father broke with his employer and resolved to become a minister of religion, entering C.H. Spurgeon’s Pastors’ College to qualify himself. This meant dispersing the family and Walter was sent to live with his grandmother at Borehamwood, near Elstree. In 1891 they were re-united in a house at Croydon and Walter was sent to Whitgift Middle School. He was there until the end of 1895 when he gained a scholarship to the Upper or Grammar School. Meanwhile, the pastorate which his father had undertaken at Croydon met with ill success, partly no doubt because of the increasing liberalism of his teaching, and he was constrained to return to the wine business. In 1896 he declared himself an agnostic. This in no way impaired his sense of mission or the hardships, including extravagantly early rising and vegetarianism, which he imposed on his family. He turned to the doctrines of Bernard Shaw, Ramsay Macdonald and Moncure Conway without remitting any of the crusading puritanism which his self-esteem demanded.

Walter Godfrey’s schooldays he records as busy and happy and he found plenty of interests to offset the rigours of his home life. He passed the London University matriculation examination in 1898 and, for a short spell, worked in the office of C.H. Chaplin and Co.where his father was employed. Then came an offer, which had been tentatively made two years earlier, from Mr James Williams, architect, of Victoria Street to take Godfrey into his office as an articled pupil. Williams had succeeded to the practice started by George Devey (1820-86), whose country houses and gardens in the Elizabethian manner are among the most distinguished achievements of mid-Victorianism. The offer was accepted and Godfrey’s pupilage lasted for two years, during which time he explored the medieval monuments of London and the surrounding country, measured at South Kensington and Westminster Abbey and attended evening classes at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, where Henry Ricardo was teaching. In December 1900 he left Williams and took employment in the architectural section of the London County Council.

In 1901, while still not 20, Godfrey published his first archaeological article in W.J. Hardy’s Home Counties Magazine; it was on the Whitgift Hospital in Croydon. In April of the same year he was elected a member of the Survey of London which C.R. Ashbee had founded in 1894 and whose object was the publication of monographs and parish surveys to record the ancient buildings of London, then unprotected by any kind of legislation. He was at once involved in preparation for the first of the Chelsea volumes – preparation which led to his authorship of all the four volumes which appeared between 1909 and 1927. In 1902 he attained his majority, on which occasion his father gave him a bicycle and, soon after, instructed him somewhat peremptorily to leave home and fend for himself. He took a furnished room at 8 Glebe Place, Chelsea, and in September rejoined the London County Council, which he had left for a short period.

Godfrey’s ideas at this time were very much those which his father had done his best to instill. They are reflected in a few short essays published in the Reformer and elsewhere. But ethical humanitarianism is a bleak garment for a young mind and Godfrey soon threw it off. He did so, with a sense of immense relief, under the influence of Emil Reich, the Professor of History at Birkbeck College, whose lectures he attended in 1904-6. Reich’s view of history ‘opened the doors of the prison house’ and showed the way to a more optimistic evaluation of the world and one which Godfrey, with his love of nature, eagerly accepted and always retained.

In May 1903 Godfrey finally left the London County Council and returned to the office where he had served his articles. Mr Williams had retired and his partner, Edmund Wratten, conducted the practice and took on Godfrey as an assistant under a two-year agreement. Before the term was out, however, Wratten had married Godfrey’s sister, Gertrude, and the two men had formed a business partnership as successors to James Williams, commencing practice in the old offices at Carteret Street, Queen Anne’s Gate, in the autumn of 1905.

The prospects of the partnership were not brilliant. With time on his hands for study Godfrey entered for the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Essay Medal. The set subject was ‘The Life and Work of a Great Victorian Architect’ and Godfrey chose Devey. He won the medal. It occurred to him that the essay might be expanded and that a round of visits to Devey’s country houses might serve the double purpose of gleaning information and introducing himself as Devey’s successor to their occupants. If the scheme brought no rush of work to the office it spread the partners’ reputation among a circle of wealthy and influential people.

In June 1907 Godfrey married Gertrude Warren, to whom he had been deeply attached since he was 19. The story of his first rejection, of Miss Warren’s engagement to another man and of the final outcome leading to an ideally happy marriage lasting for nearly fifty years, is touchingly told in the memoir. After a honeymoon at Les Andelys, the young couple settled in a cottage at Radlett.

Godfrey at this time was busy on illustrations, notably for Garner and Statton’s Domestic Architecture in England in the Tudor Period, published by Batsford in 1911. For this work he produced an elaborate elevation and perspective of the oriel window at Crosby Hall, Bishopsgate, then threatened with demolition. Simultaneously was he contributing an architectural study on the Hall to Philip Norman’s monograph on the building. This appeared in 1908 and aroused the interest of Professor Patrick Geddes of Edinburgh. Geddes asked Godfrey if he could rebuild the hall on a new site and the reply was that he could. The roof and the numbered stones had been accepted by the London County Council for re-erection at somebody else’s expense; and the Town and and Gown Association, with which Geddes was associated, were able to provide a plot of land in Chelsea, part of which had been built upon to provide the headquarters for the British Federation of University Women. Godfrey undertook to rebuild the hall for £7000, and eventually, after some very anxious moments, saved £120 on the contract. The hall was rebuilt in the course of 1909-10 and opened in the latter year by John Burns. It was the architect’s first important commission and its success was complete.

Between 1907 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Godfrey’s work was an interesting mixture of archaeological research and practical building. To 1907 belongs the graphic reconstruction, in collaboration with William Archer, of the Fortune Theatre in drawings which, first reproduced in the Tribune for 12 October of that year, have become famous as illustrations of Shakespearian stage history. Also in 1907 he started lecturing to a class, mostly of pupil teachers, at the Municipal Institute, West Ham. In 1909 appeared the first volume of the Chelsea series in the Survey of London already mentioned. The History of the English Staircase and the History of Architecture in London were published in 1911; in 1913 came the valuable collection of articles by Godfrey and his friend A.W. Clapham, Some Famous Buildings and their Story; and, in 1914, Gardens in the Making. As an architect, Godfrey was responsible during this period for a house at Westerham for Mr Charles McDermind (1909-10), for several works of alteration and restoration and, just before the war, for the reconstruction of the Gambrinus Restaurant near Leicester Square.

The war found Godfrey working for part of his time as an investigator for the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, who Buckinghamshire volumes were then in preparation. In May 1915 he was transferred with the commission’s staff to the Ministry of Munitions. Rejected as unfit for active service, he remained with the ministry, dealing with contractors’ unpaid accounts in the Accounts Division, until November 1919. He found time, meanwhile, to edit the London Survey Committee’s monographs on Morden College and Eastbury Manor House and was instrumental in persuading the owner of the latter to preserve it and relinquish it to the National Trust, provided guarantors were found for the purchase. In 1915 he was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.

Released from his wartime duties at the end of 1919, Godfrey returned to the more congenial labours of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, at the same time seizing such opportunities as presented themselves of resuming the practice of architecture. He was now living in Sussex, where he had taken a house at Buxted in 1915 and to which county, its landscape and antiquities, he remained devoted for the rest of his life. Three children – two daughters and a son (Walter Emil) – had been born before the war; in 1921 a third daughter was born, and in 1923 the family moved to Bull House, Lewes, a medieval building which Godfrey had restored for an earlier occupant, the Sussex iron master Mr John Every. They lived there until 1928.

Immediately after the war Godfrey devised an interesting system of ‘Service Heraldry’, proposed as a means of pictorially recording personal careers in the services. Frowned on by professional heralds, it was supported by, among others, Rudyard Kipling, but was eventually dropped. He was soon completely absorbed in architecture. He built a house at Currer Wood, Ashtead, for Miss Mary Lupton in 1919 and about the same time was engaged in converting several ancient and attractive inns for Mr Alexander Part, the initiator of Trust Houses Ltd. By 1922 he and his partner were conducting a busy office with three assistants and at this time he converted a chapel in Eton College as a war memorial and also built the chapel at Goldings (1923-4), a house by Devey which had been taken over by Dr Barnado’s Homes. He restored Burford Priory for Mr J.E. Horniman and Dean’s Place, Alfriston, for General Sir Herbert Lawrence, both in 1923. The Burford work, involving many difficult decisions, was one in which he took a particular pride. He designed the gardens at Kidbrooke Park, for Mr and Mrs Hambro, in 1924. In 1925 Godfrey’s partner, Edmund Wratten, suddenly died and the burden of the practice fell squarely on his shoulders. Small houses in Sussex and elsewhere and a great variety of works of alteration and restoration made up the bulk of the work. There was less opportunity now for research and literary work, but in 1928 and 1931 appeared the two volumes of the Story of Architecture in England, richly illustrated from a great variety of sources. From 1928 till 1931 Godfrey acted as Honorary Secretary of the Royal Archeological Institute.

The prosperity of the 1020’s ended in the slump of the early 1930’s which, although it did not affect Godfrey’s architectural practice as severely as some, induced him to give up the London office, then at 18 Queen Anne’s Gate, and, in May 1932, move down to Lewes, to the charming house, no. 203 High Street, which he had taken a few years earlier. Within six months, by extraordinary good luck, he was offered the most inspiring and lucrative task of his career – the restoration of Herstmonceux Castle for Sir Paul Latham.

The restoration of Herstmonceux proceeded for the next two years and its satisfactory completion Godfrey regarded as the apex of his career. This was followed by some other important restorations, including Swanborough Manor, near Lewes, for Mr C.A.H. Harrison and Court House, Barcombe, for the hon. Sylvia Fletcher-Moulton. Two new houses, Jugg’s Lane, Kingston, Lewes, for Miss Edith Barran, and Little Rowfant for Mrs Rimmington-Wilson, were also of this time; but it was restoration work, together with many antiquarian projects, notably in the form of papers contributed to the Sussex Archeological Collections and Sussex Notes and Queries which formed the main part of Godfrey’s activities up to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. By this time (1936) he had moved to Lewes House, a fine Georgian mansion in the High Street, threatened with demolition.

In 1940, when the first bombs began to fall on London, concern was felt that there was no central organization responsible for securing records of historic buildings which might be damaged by aerial attack. A conference was held at the Royal Institute of British Architects on 18 November, at which eighteen societies were represented. The eventual upshot was the formation of the National Buildings Record, with Lord Greene, Master of the Rolls, as its chairman and Godfrey as its salaried Director. The task of the new body was to co-ordinate existing records and to obtain new records in the form of drawings and photographs where necessary. The project was one for which Godfrey was peculiarly well qualified after nearly 40 years’ connection with the London Survey Committee, an intimate connection with the Graphic Records Committee (formed in 1931) and an exceptionally wide knowledge of architectural records in general. From February 1941 until his retirement in 1960 the operation and development of the National Buildings Record were the main concern of his life. The work began in a room in the Royal Institute of British Architects’ building, but in September 1941, the Record moved to All Souls’ College, Oxford, where Godfrey had rooms and shared the Common Room life of the Fellows. After the war the Record moved back to London. Godfrey had taken a house in the village of Steventon near Abingdon and this remained his home till his death.

Between 1945 and his death in 1961 Godfrey was active in every sphere connected with the study and preservation of historic buildings. He had been appointed a member of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments in 1944 and of the Advisory Committee on Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest in the Ministry of Housing and Local Government in 1945. He was vice-president of the Society of Antiquaries in 1947-51 and of the Council for British Archaeology in 1952-54. As joint honorary editor of the London Survey Committee (an office he had held since 1934) he edited the last parish volume – the fourth on St. Pancras parish – for which the committee was responsible; it appeared in 1952. He also prepared the monograph on St. Bride’s, Fleet Street (1944) and was responsible for that on the College of Heralds, published after his death.

He became chairman and honorary editor of the London Topographical Society in 1928 (vol XIV), continuing to act until volume XXI of the Record, published in 1957, a volume which contains his own account of the work of the London Survey Committee, 1894-1952, as well as an admirable photograph of himself, at the age of 44, taken by Mrs Gillick.

Besides the monographs mentioned above, Godfrey wrote two books after 1945. The first, Our Building Inheritance (1944), which in the nature of a popular introduction to the beauties of historic architecture, was very successful. The other, The English Almshouse (1955), was a summary, which he was prevailed upon to write, of a subject which had been a life study of his but which he now realized he would never be able to treat at any length. A new, much enlarged, edition of the History of Architecture in London appeared in 1962.

But the most striking achievements of Godfrey’s later years were, undoubtedly, the rebuilding of the old parish church at Chelsea, almost completely destroyed by a bomb in 1941, and the restoration of the Temple Church, severely damaged by fire in the same year. In both these great works of restoration, he had the assistance of his son, Emil. The Chelsea church was the building on which he had first exercised his gifts as an antiquary and recorder as a young man in his mid-twenties. That it stands today, nearly in its original form and with much of its monuments replaced, is due as much to the fastidious care bestowed on the recording as to the sympathy and skill of the rebuilding.

In 1950 Godfrey was appointed C.B.E. In 1955 he suffered a severe blow in the death of his wife. His own health was not good and in 1960 he was obliged to relinquish his conduct of the National Buildings Record. He died in a nursing home in Oxford on 16 September 1961. Cremation took place at Oxford on 21 September and the ashes were laid in the Lewis House vault at All Saints’ Church, Lewes. A memorial service attended by many relatives and friends and representatives of various bodies was held at Temple Church on 4 December 1961.